Ising_Model

This is a Conformal Field Theory “Hello World” project. Apparently the symmetry group of the ising model around its phase transition is actually the Virasoro group. Therefore we can conformal field theory our way into a nice description about it, just to play around with the fundamental objects there.

We begin with a classical treatment of the model to fully define some terminology (but also because it is fun) and then move on to identify how the matching with the CFT description occurs.

Classical Treatment

Here is a brief overview the classical treatment of the 2D Ising model in order to find the limit at which it reduces to a quantum model.

Physical Setting

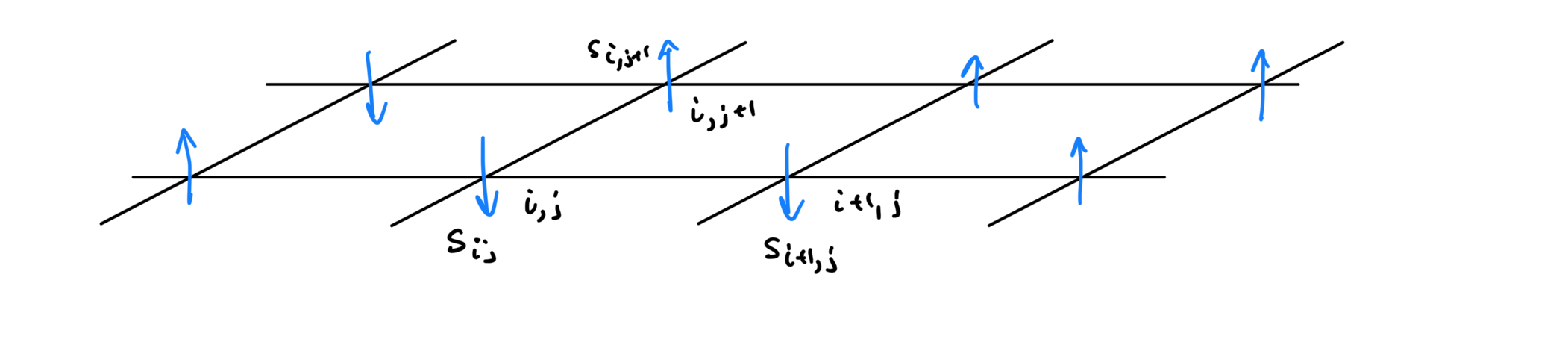

The setup is a bunch of arrows arranged in a lattice that can interact with their nearest neighbors. A picture is the following, where we have a 2D lattice and an arrow attached at each point.

To build a mathematical description of the model, we can first identify a suitable configuration space. Let’s start with a finite lattice 2D lattice that contains a total of

Notice that

The Hamiltonian in this case must capture the interaction of the neighboring spins. For some point

where

Magnetization in the Canonical Ensemble

In the Canonical Ensemble, the partition function is given by

Classically the magnetization is given by the average of the particles aligned in the up direction like so

The phase transition also appears on the susceptibility which is given by

With some algebraic manipulation we can get that

OK! All of this is not quantum, but check out that

The cool thing is that

We will use CFT to calculate these correlation functions.

Mean Field Theory During Transition

Quantum Treatment

Ok, everything up to now has been fun, but it has mostly been background so that when we treat Ising in CFT we can be like OH COOL! Look at these conformal weights! They are the same as the classical ones! Now we will proceed with establishing a correspondence between the classical Ising model and some CFT. We do this by establishing a connection between the classical treatment and the quantum treatment and then we take a continuum limit of the quantum model to some CFT. So before we do everything there let's understand the Quantum Ising model.

Classical Starting Point

This whole section can be skipped if you don't care about rigorously motivating angular momentum in classical Hamiltonian mechanics.

Let's first consider the single spin case in 3D. We have a magnetic moment

The only quantity of interest is this angular momentum vector

For the purposes of this construction we will consider the spin as a point in

where

where

The first thing that we want to show is to find the momentum map of the sphere.

Proposition: The restriction on the sphere of the fundamental representation of

Proof: We will show that

In particular we want to show that

We can now calculate that

In fact here is a picture of their Hamiltonian vector fields for

Now we can move on through geometric quantization to produce the Hilbert space associated to this thing.

Hamiltonian

Now consider the Hamiltonian of that spin system. If the point on the sphere is an angular momentum, then on an external magnetic field

We can actually plot this Hamiltonian right here,

Where the phase space is shown in translucent gray and the Hamiltonian (

Interestingly, we can think of what happens when we have

with the canonical product topology and symplectic form.

We want those to interact with each other, so the way we will do this is using graphs.

Definition: Given a connected graph

Proposition: In a nearest neighbor interacting system there exists a map

Proposition: In a nearest neighbor interacting system there exists a map

This map is called the adjacency map and it is a permutation.

Now, we can play with the interaction terms. We will restrict our attention to nearest neighbor interacting systems because they have an interesting relation with the quantum mechanical and field theoretic models. In particular, let's say that the spins interact with each other based on their

Proposition: Given a map

Proof: The map is

Proposition: The map

In the case the system is nearest neighbor, we have that

In other words we can introduce the following interaction term:

where

for some

If the external field is pointing in the

Construction of Hilbert Space

Performing canonical quantization we see that

Proposition: The single particle Hilbert space

Now we can proceed by defining operators appropriately through geometric quantization by identifying the linear operator

We can then create the

previousDefinition: The

So now we have the Hilbert space constructed and we can proceed with the Hamiltonian.

Definition: The Quantum

where

Quantum to Classical Correspondence

The item of interest that will facilitate the correspondence of the the classical and the quantum theories is the partition function. We have calculated it for the 2-dimensional Ising model in the previous section, so we can try to evaluate it for this one.

The partition function is given by

for some

which are non-commuting operators. We could use Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff to obtain the result, but that is insane. Anyway here is the proposition.

Proposition: The partition function is given by

for some

Quantum Field Theory

Having the quantum mechanical model it is time to "take the continuum limit" and obtain a quantum field theory for it. This is done through the Jordan-Wigner transformation that we will explore in mode detail. What we will derive, is a prescription to increase the number of spins in such a way that it limits to the CFT of a free fermion.

To do so, we will define linear operators

Proposition: These operators have the following commutation relations

The cool thing is that we can now rewrite the Hamiltonian.

Proposition: The Hamiltonian for the 1D Ising chain can be written as

Proof: Plug it in and cry.

Bosonization

A convenient tool to analyze the Ising model